FAIR Girls Admin

April 2021

Executive Director Letter – April 2021

Dear Friends & Supporters,

Happy Spring! It is hard to believe that it has been a year since COVID changed our world on almost every level. It has been an unimaginably difficult year in so many respects, but it is hard not to begin to see the light at the end of this long, dark tunnel. Spring is about new beginnings, emerging from the cold dark days of winter with a new perspective and renewed resolve. As the cherry blossoms bloom around the area, I am reminded that hope springs eternal even after the coldest of days. It is truly heartening that we may be starting to turn the corner with the help of the vaccination rollout. Even as we dare to believe better days are ahead, those of us on the frontlines of the anti-trafficking movement know that we are just beginning to see the true negative impact of the isolation, economic hardship, and increased online presence of youth caused by this pandemic. Even as we take a deep breath of fresh, spring air, we take stock and prepare ourselves for what still lies ahead and ensuring that we are here for the survivors that need us every day.

I cannot tell you how proud I am of our small but mighty FAIR Girls staff. They have gone above and beyond in circumstances that we would never have dreamed of. We are so proud that we have been able to keep our services available and accessible to survivors in need throughout the pandemic. It was never a question of whether we would, but rather, just figuring out how to do so safely and effectively. But we didn’t do it alone either! We could not have done it without the invaluable support of our wonderful and generous community partners and supporters. From donated safe extended-stay hotel rooms for survivors to quarantine in, to providing holiday meals and gifts for our Vida Home residents to purchasing emergency grocery gift cards for our youth clients whose families are suffering food scarcity during the pandemic, you have risen to the call to action every step of the way with us. Without your generous support and belief in our mission, we would not have been able to meet the needs of the flood of survivors who came to us for help during the pandemic.

And just like the courageous girls and young women we work with every day, we have not just survived this past year, we found ways to thrive too. We have strategically grown and made ourselves stronger despite the challenges we faced this past year. We are so excited about our new and expanded Drop-in Center opening this summer. Our new space will allow us to provide more survivors with expanded services and programming, including in-house therapy, hot meals, free laundry services, and economic empowerment programming in our dedicated workforce development space. While it has been a long road, we know being able to provide access to “one-stop-shop” comprehensive services for survivors is going to be a game-changer. Stay tuned for all of the exciting updates in the coming months!

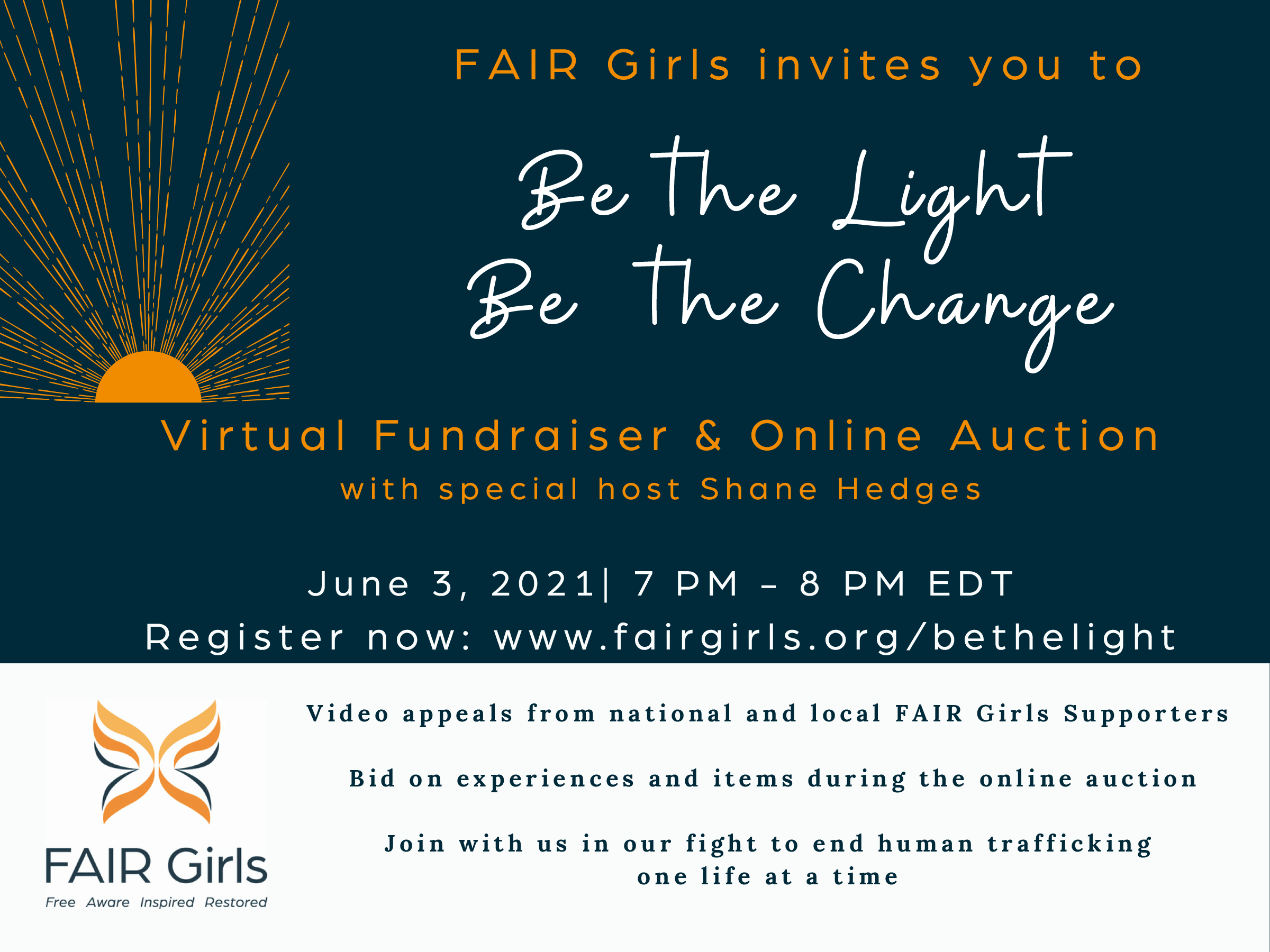

I am also excited to announce that we are hosting our second virtual fundraiser LIVE on June 3 from 7:00 pm – 8:00 pm eastern. Be the Light, Be the Change is this year’s theme and we cannot think of a better one given all that we have been through and all the positive change we know we can make working together. It will be an uplifting and empowering hour, including video appeals, video performances, our online auction, and so much more. This is FAIR Girls’ biggest fundraiser of the year, so please mark your calendars and plan to join us for this celebration.

Thank you for your continued support and belief in our mission of ending human trafficking, one life at a time.

Be well,

Erin B. Andrews

Executive Director, FAIR Girls

Capitalism & Human Trafficking

With global inequality worsening and disparities becoming more prevalent in capitalist systems, vulnerabilities are being exacerbated. Basic necessities are being commodified: workers endure horrendous conditions while being underpaid, and vulnerable populations are illicitly bought and sold for nonconsensual sexual services.

Human trafficking is a booming business, now estimated to be over a 150 billion dollar industry (“Profits and Poverty”). Under capitalism, trafficking and exploitation thrive. Capitalism enables human bodies, especially those in vulnerable or unstable situations, to be seen as highly expendable, reusable, and profitable objects by those looking to exploit. Traffickers often hone in on these vulnerabilities using Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs to fill an emotional, psychological, and or physical need that the targeted individual is in search of. This may be providing a safe place to stay, a loving relationship, or a sense of belonging. Through this grooming process, the targeted individual is reduced to a means to an end that will ultimately result in their exploitation and the trafficker’s profit. Moreover, many traffickers use legal industries, such as public transportation, hotels and motels, social media, and banks, to aid the recruitment and continuation of trafficking. And while industries that intersect with human trafficking, like hotels and motels, are beginning to implement trafficking awareness employee training, many still do not have the proper training for employees or intentionally turn a blind eye to the exploitation in fear of losing traffickers’ business.

With capitalism being an economic and political system where “a country’s trade and industry are controlled by private owners for profit, rather than by the state” (Oxford Languages), private ownership and profit maximization are key drivers in our community. In regards to trafficking, human bodies and “services” are commodified and sold through force, fraud, or coercion for profit.

Looking at trafficking through a simple supply and demand economic model, there is a supply of product or service (trafficked persons) fueled by a demand (buyers) and private intermediaries to facilitate the exchange (traffickers) (Wheaton et al. 2010, 115). Every trafficker operates as their own business owner to maximize profit with an individual demand curve that fluctuates depending upon how “unique” their “product” is in comparison to other competitors’ (Wheaton et al. 2010, 124). Dr. Justine Pierre’s research on trafficking in the Caribbean articulates this point through interviewing over 300 human traffickers. The interviews reveal that all of the traffickers view themselves as business people rather than human rights abusers (Williamson). In order to maximize profit, traffickers may choose to target higher income brackets and therefore demand higher prices from buyers in exchange for the (Kara 2010). Alternatively, traffickers may focus on lower-income brackets with lower prices but supply a larger quantity of “product,” thus driving up the demand for sexual services (Kara 2010). In either case, profit maximization is at the forefront.

The role that race plays in trafficking and capitalism is another aspect that cannot be ignored, starting with the Transatlantic slave trade that ran parallel to the rise of European capitalism. Africans were bought by Europeans to work on American plantations—and later the Caribbean and Eastern African plantations—harvesting various raw materials like sugar, coffee, and cotton that would be sent to Europe who would then ship guns, wine, and textiles to Africa in return (Transatlantic Slave Trade 2021). Black and Brown bodies were rendered expendable forms of labor that could produce capital for profit. While the Transatlantic slave trade no longer exists today, its long-term impact is haunting and ever-present. Black, Brown, and Native communities are disproportionately more likely to experience food deserts, poverty, disconnection from education systems, lack of appropriate and sufficient health care, and family instability than white communities. Coupled with the historical commodification and hypersexualization of Black women and girls, communities of color, especially Black communities, are left particularly vulnerable to trafficking. In a 2018 two-year FBI report on suspected country-wide human trafficking incidents, 40% of sex trafficking victims were Black (Louisiana Department 2018) despite only 13% of the US population identifying as Black (United States Census Bureau).

From an economic perspective, there are two ways that the human trafficking market can be disrupted: increasing the cost or risk to traffickers or reducing the demand for cheap labor and sexual services (Wheaton et al. 2010, 130-131). Ideally, “if real-world prices could be doubled and achieve a decrease in demand . . . the profitability of the sex trafficking industry would be severely compromised” (Kara 2010, 37). From a human rights and preventative education perspective, conversations surrounding trafficking and exploitation need to become more widespread. Because it is unlikely that demand for commercial sex or cheap labor will decrease by itself, support to vulnerable populations must be extended to provide resources and empowerment. FAIR Girls’ “Tell Your Friends” multimedia prevention education curriculum seeks to prevent youth from entering the world of sexual exploitation and prevent system penetration. By providing information to middle and high school-aged youth regarding risk factors, grooming techniques, and healthy relationships, in an age-appropriate and engaging manner, youth are empowered to stay safe from exploitation and victimization and help their friends stay safer. Additionally, there needs to be an increased focus on and emphasis on “people over profit” to continually instill human dignity and humanity into every educational, interpersonal, and business framework we support. If people are viewed as a product rather than an individual, exploitation of vulnerabilities will undoubtedly continue.

References

- Kara, Siddharth. 2010. Sex trafficking: inside the business of modern slavery. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Louisiana Department of Children and Family Services. 2018. Human Trafficking, Trafficking of Children for Sexual Purposes, and Commercial Sexual Exploitation: Annual Report.

- “Profits and Poverty: The Economics of Forced Labour.” 2014. Ilo.org, May. doi.org/978-92-2-128781-0.

- “Transatlantic Slave Trade” 2021. Encyclopædia Britannica. www.britannica.com/topic/transatlantic-slave-trade.

- “QuickFacts: United States.” 2019. Census Bureau. United States Census Bureau. www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/RHI225219#RHI225219.

- Wheaton, Elizabeth M., Edward J. Schauer, and Thomas V. Galli. 2010. “Economics of Human Trafficking.” International Migration 48 (4): 114–41. doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2435.2009.00592.x.

- Williamson, Celia. 2021. “Episode 81: I’m not a Human Trafficker, I’m a Businessman: The Perspective of 342 Human Traffickers” Dr. Celia Williamson. February 2, 2021. celiawilliamson.com/

“Be the Light, Be the Change”

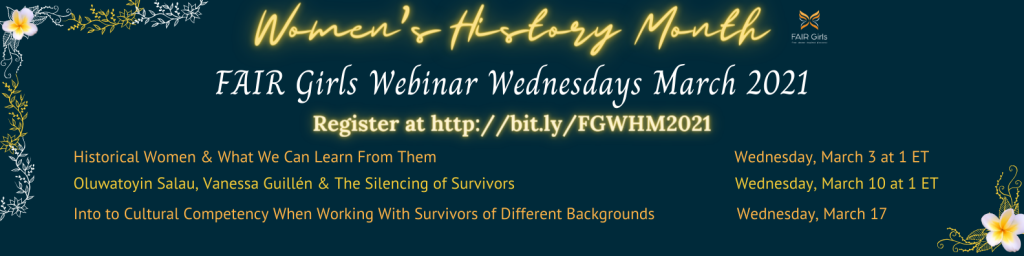

Women’s History Month Webinars

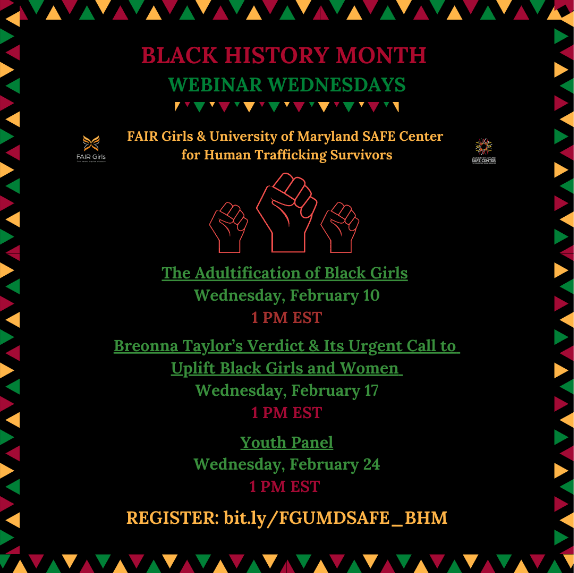

Please join FAIR Girls for a special Black History Month Webinar Wednesday Series!

FAIR Girls, in partnership with the University of Maryland SAFE Center for Human Trafficking Survivors, is pleased to invite you to our Black History Month Webinar Series!

Register here: bit.ly/FGUMDSAFE_BHM

Please feel free to contact Jasmine Morales at jmorales@fairgirls.org if you have any questions.

Injustice Anywhere is a Threat to Justice Everywhere

“Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred.” For many of us, these words by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. resonate now more than ever. To celebrate Dr. King’s life at such a tumultuous and unsettling time in our nation’s history seems almost paradoxical. King’s measured leadership, drive for justice, and commitment to love feels glaringly vacant in recent weeks, most notably as we witnessed a violent white mob terrorize our legislators and wreak havoc on our capital. The same volatility of white supremacy and racist anger that King worked so tirelessly to address sadly still persists today, and these events highlight the urgency with which we must continue Dr. King’s extraordinary work.

Often much more radical than most of white America would care to admit, King, organized for more than equality and integration. His goal, for himself and his people, was always freedom. He recognized that true freedom is incompatible with poverty and exploitation. Today, FAIR Girls knows this remains true. According to Polaris, more than 4,000 victims and survivors contacted the national trafficking hotline in 2019 alone. In actuality, we know that rates of trafficking are much higher in our communities as human trafficking is a notoriously underreported crime impacting already marginalized populations. Freedom remains elusive for far too many girls and young women trafficking survivors.

For Black girls and women, the statistics are even more disturbing. Polaris reports Black girls in Louisiana comprise nearly half of all CSEC cases though they make up less than 20% of the state’s youth population. This confirms what FAIR Girls’ staff and many anti-trafficking advocates already know: Human trafficking is a racial justice issue. Many of the unjust systems King fought against sadly remain in place today and directly contribute to the disparate rates of trafficking for girls and women of color. Generational poverty, over-policing and criminalization, and the lack of economic opportunity all continue to impact communities of color disproportionately.

As we face the hatefulness, violence, and divisiveness plaguing our communities today, Dr. King provides us with a guide to navigate our world with both empathy and peaceful but powerful resistance. And as we can learn from Dr. King, we can also learn from the young women survivors of human trafficking we work with every day. At FAIR Girls, we see the brave resilience and inspiring perseverance that empowers survivors on their long and challenging healing journey. In the face of violence, adversity, and fear, they remind us by way of example, to stay the course, one dedicated to justice and freedom.

Though it’s easy to slip into feelings of hopelessness amid the chaos and hatred of our political landscape, we must recognize that inspiration for change comes in various forms. Sometimes it’s the outspoken charisma and moral direction of a figure like Dr. King. Other times it’s the quiet persistence of young women and girls rebuilding their lives. Though King noted, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere,” it seems the opposite ought to be true as well. Justice and freedom for survivors of trafficking brings all of us closer to a world of true freedom and peace.

December 2020

Amplified Risk Factors to Human Trafficking Experienced by the LGBTQIA+ Community

One of the most terrifying aspects of Human Trafficking is that everyone is at some level of risk. There are, however, certain factors that can make individuals more vulnerable to falling prey to traffickers. The list of risk factors is extensive, but things like poverty, political conflict, and exposure to previous trauma are some of the most discussed. Poverty, for instance, increases an individual’s desperation, which is often manipulated by traffickers with promises of a better life. Political turmoil, and the environment of fear that comes with it, can also amplify an individual’s vulnerability to promises of safety and economic security from manipulative traffickers. Prior trauma may lead to low self-esteem, lack of a support system, and an increased need for acceptance – all vulnerabilities recognized and preyed upon by traffickers.

While these risk factors are capable of affecting any member of our society, certain disenfranchised groups face them at significantly higher rates. One such group is the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer/Questioning, Intersex, Asexual, + (LGBTQIA+) community. Take previous trauma, for instance. Homophobia and intolerance mean that LGBTQIA+ individuals face stigmatization, ostracization, and abuse at disproportionately higher rates. According to a 2010 CDC NISVS (National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey) on the rates of rape, physical violence, and stalking by an intimate partner, members of the LGBTQIA+ community are at a far higher risk for victimization. Lesbian and Bisexual women faced victimization at rates of 44% and 61% respectively, compared to 35% for heterosexual women. Gay and Bisexual men were victimized at rates of 26% and 37% respectively, compared with 29% of heterosexual men. Further, according to the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey, 47% of transgender Americans have faced violence at some point in their lives.

Poverty is also disproportionately prevalent in the LGBTQIA+ community. In 2019, the Williams Institute of Law at UCLA conducted a national study on rates of poverty in the LGBTQIA+ community. The results found that Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender individuals have a poverty rate of 21.6% compared to cisgender straight people, who have a rate of 15.7%. For context, this disparity in poverty rates could be due to a number of factors, including, employment discrimination and historical bans or restrictions on marriage (marriage often brings financial benefits with it).

All of these risk factors are even further amplified for LGBTQIA+ youth. This is largely due to rejection by their families and communities. While being socially and familially ostracised on account of one’s sexuality is harmful to anyone, it is especially dangerous for youth as they rely upon that support system for the essential things they need to live (eg. shelter, food, water, medication, etc.). As a result of this familial rejection and at-home abuse, 40% of the 1.6 million homeless youth in the United States identify as Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, or Transgender according to the Williams Institute of Law at UCLA. This often leads to feelings of desperation in these youth and forces them into “survival mode’ to acquire basic necessities such as shelter, food, and toiletries. According to the Polaris Project, this desperation leads to LGBTQ youth being 3-7 times more likely to engage in commercial sex work to gain these necessities. This type of survival behavior is indeed child sexual exploitation. Per the U.S. federal law, any time a child engages in commercial sex it is considered the Commercial Sexual Exploitation of a Child (CSEC), as minors cannot legally consent to engage in commercial sex. This survival behavior and resulting sexual exploitation often further stigmatizes these already marginalized youth as they are labeled as “prostitutes” or “sex workers” by members of their community or law enforcement.

Importantly, LGBTQIA+ individuals who also identify as members of the Black, indigenous, or other communities of color (BIPOC) community and other non-white communities face even higher levels of vulnerability to risk factors due to their compounded oppression and marginalization for being both LGBTQIA+ and BIPOC/non-white.

While the data makes clear that members of the LGBTQIA+ community are at a far higher risk of being victimized by traffickers, it is also clear that they face significant barriers in accessing the services, support, and resources they need to exit their trafficking situations due to deeply ingrained societal biases and misconceptions against LGBTQIA+ individuals.

Let’s take the medical field as an example of how society often fails these LGBTQIA+ trafficking victims. According to an article published in the Annals of Health Law magazine in 2014, 88% of victims of trafficking or CSEC will visit a medical provider during their victimization. Interactions with medical or healthcare professionals could be for an array of reasons, ranging from injuries from sexual or physical abuse to drug overdoses to treatment for sexually transmitted diseases. According to the Center for American Progress (CAP), LGBTQIA+ people are disproportionately mistreated by healthcare professionals than their cisgender straight counterparts. According to a CAP survey, 8% of LGBQ respondents and 29% of transgender respondents indicated a doctor refused to see them based on their sexual orientation or gender identity respectively. Further, 6% of LGBQ people and 21% of transgender people said a doctor or other health care provider used harsh or abusive language while treating them. Further, 8% of LGBTQ respondents indicated they avoided or postponed getting necessary medical care due to previous experiences of disrespect/discrimination at the hands of a healthcare worker. This data makes clear that LGBTQIA+ victims of trafficking and CSEC often do not get the care they desperately need, but also the sad reality that they may not even seek medical care in the first place due to these negative experiences.

Bias within Law Enforcement agencies can also disproportionately negatively impact LGBTQIA+ individuals, including LGBTQIA+ victims of trafficking. A 2014 study conducted by the UCLA Williams School of Law yielded important findings with regards to the relationship of the LGBTQIA+ (and HIV+) community and law enforcement. According to the survey, 73% of respondents had face-to-face contact with police in the past five years. Of that 73%, 21% indicated an law enforcement officer had treated them with a hostile attitude and 14% indicated a law enforcement officer had verbally assaulted them. Moreover, all of these numbers were consistently higher among People of Colour, transgender, and gender-nonconforming respondents specifically. Another report conducted in 2013 found that 48% of LGBT survivors of violence who interacted with police said they experienced ‘police misconduct’ (incl. excessive use of force and entrapment). A 2011 study found that 22% of transgender respondents had been harassed and 6% had actually been physically abused by a law enforcement officer.

The inherent and dangerous bias that this data demonstrates consequently negatively impacts how crimes involving LGBTQIA+ victims are handled by law enforcement agencies. In 2014, a report on a national survey of 2,379 LGBT and HIV+ people found that over a third of LGBT/HIV+ crime victims’ cases were not properly addressed.

This systematic mistreatment, understandably, leads LGBTQIA+ folks to be wary of seeking assistance from law enforcement. In the 2011 survey, for instance, 46% of transgender respondents indicated feeling uncomfortable seeking police assistance. The 2013 survey found that only 56% of LGBTQ and HIV+ survivors of hate-based violence reported those instances to the police. Similar to healthcare and medical agencies, the danger of LGBTQIA+ related bias in law enforcement agencies lies in LGBTQIA+ victims not reporting their victimization, not being properly identified, and not being treated humanely as they seek safety and protection.

To illustrate the complex issue of implicit bias, let us explore the following hypothetical scenario:

Marvin is an adult gay man who acts and dresses more femininely. Under the coercion and control of a pimp, he is working as a commercial sex worker in a city where prostitution is illegal. While on patrol, two police officers see Marvin engaging in commercial sex. Given their implicit biases against gay and transgender men (for instance, the misconception that they are all hypersexual), the officers automatically assume that Marvin chose to work as a prostitute and do not even consider that he may be a victim of sex trafficking. As a result of these implicit biases, Marvin’s victimization will likely go unrecognized and unaddressed, and perhaps even more concerning, will likely lead to Marvin’s criminalization. Further, as a result of not viewing Marvin as a potential victim, these law enforcement officers have missed the opportunity for positive intervention and referral of Marvin to essential victim services.

Human Trafficking is one of the most complex issues plaguing our society today. Part of that complexity has to do with varying vulnerabilities across different demographics. The LGBTQIA+ community, on account of higher rates of poverty and previous exposure to trauma, in particular, is one demographic that is at a significantly higher risk of falling prey to traffickers. Moreover, the ability of LGBTQIA+ identifying individuals to seek help and exit their trafficking victimization is impaired by inherent bias within many of the essential service systems and agencies that these individuals intersect with on a daily basis. Armed with this data and knowledge, the next step is for the anti-trafficking movement to be actively engaging policymakers and related stakeholders in addressing these biases, protecting LGBTQIA+ individuals from exploitation, and reducing barriers to identification and specialized services for these most vulnerable victims.